Betsy Powell, Peter Small, Toronto StarAugust 2, 2008

Cases show double standard, critics sayA Toronto judge acquits two men of firearms charges, finding that police testimony was “unreliable, likely false.” In another courtroom, a judge convicts a prominent community activist of perjury, ruling that she deliberately misled the court.

These two recent court cases highlight the rarely prosecuted offence of perjury. For some in the legal community, they also raise questions about double standards, how often police lie on the stand and how infrequently they face charges.

This past week, supporters of activist Valarie Steele, found by a judge to have lied to get her son released from custody, wondered aloud if she should have been charged at all.

Also this week, the province’s Special Investigations Unit announced it is probing the case of Shayne Fisher, 24. Fisher and another man were acquitted after Superior Court Justice Brian Trafford ruled in June that the men were “physically abused” by Toronto police drug squad officers during a raid.

“Important parts of the evidence tendered against the defendants, at the preliminary hearing and at trial, have been found by the court to be unreliable, likely false,” Trafford wrote.

Defence lawyers point to other examples of judges acquitting people because of unreliable testimony from police. It even has a name: testilying.

A case often cited is that of Kevin Khan, acquitted on drug charges by Justice Anne Molloy in 2004. She found two Toronto police officers, including Det. Glenn Asselin, used racial profiling when they stopped Khan and later “fabricated” evidence.

“I quite simply do not believe the evidence of the officers,” she wrote in her judgment.

Asselin was investigated internally and cleared. He remains with the force as a detective.

Then there’s the high profile case of the three officers who testified at the 2005 assault trial of Toronto police officer Roy Preston.

Ontario Court Justice Peter Wilkie convicted Preston after finding him to be “neither credible nor reliable.”

Wilkie also found the evidence of the three officers who testified on Preston’s behalf to be “vague,” “contradictory” and “fundamentally unreliable.”

Preston went to jail after losing his appeal. He is suspended without pay and faces disciplinary charges and could be fired.The three officers were investigated and cleared by their superiors.

In the Steele case, police wiretaps caught the activist saying her son, a witness in the Jane Creba murder case, wasn’t adhering to his bail conditions on unrelated charges. In court, she had indicated the opposite and was subsequently convicted of perjury.

Supporters argued she was being punished for her son’s unwillingness to co-operate.

Academics throughout North America have found the police culture encourages lying.

“When officer self interest, and/or the bond of the `thin blue line is challenged,’ as in a disciplinary proceeding, overt lying is widely recognized as a common occurrence,” Dianne Martin, the late Osgoode Hall law professor, wrote in a 2001 paper.

Defence Lawyer Edward Sapiano says police knowingly commit perjury because of what he calls “noble-cause perjury.”

“Police knowingly give false testimony to facilitate the prosecution and to ensure the conviction of persons the police ‘know’ are guilty. Because police so easily get away with noble-cause perjury … police quite reasonably believe they are being encouraged to lie by the administration of justice itself.”

An assistant Crown attorney, who spoke on the condition of anonymity, didn’t disagree.

“You would expect … police witnesses to have a stronger regard for the oath but people lie in court all the time, police officers included.”

“There is an attitude that the legal system is just a bunch of bulls— invented by lawyers and … the oath doesn’t really bind anyone’s conscience, in some quarters. I’m not saying every cop is like that but I’ve certainly had the impression over the years that there are many that do feel that way.”

Gary Clewley, a defence lawyer who often represents police officers charged with crimes, says it’s “ridiculous” to suggest that judges and Crowns tolerate police perjury because officers perceive it to be a legitimate means to an end.

And just because a judge finds an officer “likely” gave false testimony, doesn’t mean he or she lied.

“There’s a world of difference between saying `I’m not satisfied sufficiently to deprive somebody of their liberty based on the evidence’ and the officers are outright liars.”Sapiano says it’s rare police are charged either internally or criminally, “even when sufficient evidence exists, and apparently only … when a defence lawyer catches them lying and it makes the front page of the newspapers.”

Christopher Downer, a former Toronto detective who used to investigate allegations of misconduct against court officers, remembers a case where two police “buddies” of a court officer charged with assault lied on the stand. “I sent a package off to internal affairs: nothing was ever done.

“No one’s aggressively going after anyone and at the end of the day nothing happens.”

“That’s not the case at all,” responds George Cowley, director of legal services for the Toronto Police Service. He points to the case of Amar Katoch, a veteran Toronto officer charged with assault, perjury and attempt to obstruct justice by his employer after a videotape of an anti-poverty protest in 2003 showed him punching a protester.

“There’s no apathy at all. We’re very concerned about comments made by judges,” Cowley said.

Katoch was acquitted by a jury last fall. The Crown is appealing.

In the Khan case, Molloy’s comments about Asselin were “troubling,” Cowley says. “We thoroughly looked into the entire matter and it was determined that there was no evidence to support either criminal or Police Services Act charges.”

While the Ministry of the Attorney General failed to respond to questions about the number of perjury charges laid against police, two Ontario police officers facing perjury charges will be in court this fall.

This month, OPP Det. Sgt. John Cavanaugh goes on trial in Toronto. In September, a preliminary hearing is scheduled in the case of Peel Region Const. Sean Osborne.

Despite these cases, the reason so few perjury charges are laid is because “it’s only in the most clearest of cases when the evidence is there” that it’s worth pursuing, says Avtar Bhangal, the lawyer who represented Sunny Bains, who Osborne is alleged to have assaulted.

“There are lots of cases where people are found to fudge the truth – it’s a different standard to actually prove that they intentionally did perjure themselves.”

Saturday, October 11, 2008

Wednesday, October 8, 2008

Flash, and give warning for Radar!

Jan 26, 2008

I'm a huge supporter of the police, but you wonder who counsels them on public relations.

They wonder why the driving public often does not co-operate with them, when they pull stunts like they did March 24 last year.

Brad Diamond, producer of TSN's Motoring 2008 (full disclosure: I appear on this show) lives near Broadview and Danforth Aves. Every Saturday morning he goes out for his usual four-buck coffee.

On this day he was driving westbound on the Prince Edward Viaduct, which connects Danforth Avenue and Bloor Street across the Don Valley. He spotted a radar trap nailing eastbound drivers, and passed it at approximately 49.999 km/h. It's there all the time so it was no surprise to him.

Of course, like most concerned citizens, he has often wondered: if radar is supposed to be a traffic safety measure, why would they run it on a bright sunny Saturday morning, on a three-lanes-each-way bridge, with excellent visibility in all directions, without a single intersection, store, home, school or in fact much human activity at all?

Surely, there are more dangerous places they could be trying to slow people down?

Let alone more important public safety initiatives the police could be doing?

Can you say "fishing hole," boys and girls?

Okay, so speeding is speeding, and speeding is against the law everywhere. But seriously.

As any concerned citizen would do if he knew someone was possibly going to break a law – especially if he knew the cops were lying in wait at the potential scene of the crime – Diamond flicked his headlights at oncoming traffic.

As you would. And as you would, most of the oncoming traffic did slow down.

Now, still assuming, perhaps naively, that slowing traffic down to make the roads safer is the objective of radar (it never works, but that's a story for another day), you'd think the cops would be happy that Diamond was assisting in their cause.

You'd think they'd want everybody flashing their headlights, all the time. Who'd take a chance at speeding then?

But no, stationed at the west end of the bridge were a couple more cruisers, pulling people like Diamond over for warning people about the radar trap.

$110 and no points.

I checked the Highway Traffic Act (HTA). I could find no reference to radar speed traps at all, let alone anything about it being illegal to warn other drivers about them. After all, traffic reporters and some websites even announce their locations.

The ticket said the offence was "flashing head beams" in contravention of the HTA, section 169.

Never mind that I have been in the car game for more than 30 years and have never heard the term "head beams."

I checked section 169 and nowhere does it mention radar traps in there.

Sgt. Cam Woolley of the Ontario Provincial Police told me that this law was put in place a few years ago to prevent "civilian" vehicles from impersonating emergency vehicles, notably tow trucks trying to bully their way through traffic to be first on the scene of a wreck.

Nothing at all about radar.

What's more, Diamond's Chevy Tahoe was not producing "alternating"' flashes of light. "Alternating" means one, then the other (just like police cars and other emergency vehicles can do), not both on/both off.

Not only was there no harm, there was no foul.

In our legal system, the legislature passes the laws, the police enforce them. It is not up to the police to make up their own laws – that's what they call a police state.

If the legislature decided in its collective wisdom to make warning of radar speed traps illegal, how hard would it be to pass an unambiguous law to that effect?

I can even help: "It is unlawful to warn other drivers about upcoming radar speed traps; never mind that they don't improve traffic safety."

Okay, the legislature might choose different wording.

The fact is, the legislature has not chosen to pass a law like this, or anything remotely like it.

If Diamond had been standing on the sidewalk holding a neon sign reading, WARNING! RADAR AHEAD!', there would have been nothing the cops could have done.

Needless to say, he decided to fight the ticket.

He contacted the prosecutor, saying the law in question had nothing at all to do with what he allegedly had done, but she said they were going to proceed with the court case.

Okay then, Jan. 10 it would be.

I had a 30-page script ready to go as Diamond's representative. (My dad, who was a lawyer, would have been proud of me. I hope.)

At traffic court, you first present yourself to the prosecutor, who asks how you're going to plead. You'd think anyone who didn't just pay the ticket in the first place and who had shown up at 9 a.m. to fight it would plead not guilty, but some didn't.

You also may have the option of pleading guilty to a lesser charge, which the first case of the morning did.

We were about fourth on the docket.

The prosecutor called Diamond to the bench, asked his name, read the charge, and asked how he pleaded.

"Not guilty, your worship,"' he responded.

Then the prosecutor said, "The police officer has no evidence in this case, your worship."'

"Case dismissed,"' said the justice of the peace.

WHAT? The police officer has "no evidence"? If he had no evidence, why the heck did he lay the charge in the first place?

The fact is, he had no law upon which to base the charge, because Diamond had not done anything illegal.

They assume that you will assume you had in fact done something illegal, fork over your cash, and they smile all the way to the bank.

Now, dad always said that in court, you take a win any way you can. But we were disappointed not to take it to trial so as to set a precedent against this little Buford T. Justice scam by the Toronto Police.

Someone more paranoid than me might suspect they did not want it to go to trial for that very reason, so as not to put their scurrilous behaviour on the trailer for all time.

Now, maybe the "no evidence"' gambit is traffic court shorthand for "the cop didn't show up." But usually with fishing holes, they expect a certain number of people to fight the tickets and schedule the cop for court duty.

I guess we'll never know.

I don't blame the individual cop here, although some of them are clearly overzealous in their pursuit of tickets, quotas, or whatever other pressures they face from their superiors.

But I think it is disgusting that police management sends cops out there to lie in wait to ticket unsuspecting law-abiding citizens when they have to know that what they're ticketing them for is not against the law.

And if they didn't know that before, they sure do now.

Toronto Star

I'm a huge supporter of the police, but you wonder who counsels them on public relations.

They wonder why the driving public often does not co-operate with them, when they pull stunts like they did March 24 last year.

Brad Diamond, producer of TSN's Motoring 2008 (full disclosure: I appear on this show) lives near Broadview and Danforth Aves. Every Saturday morning he goes out for his usual four-buck coffee.

On this day he was driving westbound on the Prince Edward Viaduct, which connects Danforth Avenue and Bloor Street across the Don Valley. He spotted a radar trap nailing eastbound drivers, and passed it at approximately 49.999 km/h. It's there all the time so it was no surprise to him.

Of course, like most concerned citizens, he has often wondered: if radar is supposed to be a traffic safety measure, why would they run it on a bright sunny Saturday morning, on a three-lanes-each-way bridge, with excellent visibility in all directions, without a single intersection, store, home, school or in fact much human activity at all?

Surely, there are more dangerous places they could be trying to slow people down?

Let alone more important public safety initiatives the police could be doing?

Can you say "fishing hole," boys and girls?

Okay, so speeding is speeding, and speeding is against the law everywhere. But seriously.

As any concerned citizen would do if he knew someone was possibly going to break a law – especially if he knew the cops were lying in wait at the potential scene of the crime – Diamond flicked his headlights at oncoming traffic.

As you would. And as you would, most of the oncoming traffic did slow down.

Now, still assuming, perhaps naively, that slowing traffic down to make the roads safer is the objective of radar (it never works, but that's a story for another day), you'd think the cops would be happy that Diamond was assisting in their cause.

You'd think they'd want everybody flashing their headlights, all the time. Who'd take a chance at speeding then?

But no, stationed at the west end of the bridge were a couple more cruisers, pulling people like Diamond over for warning people about the radar trap.

$110 and no points.

I checked the Highway Traffic Act (HTA). I could find no reference to radar speed traps at all, let alone anything about it being illegal to warn other drivers about them. After all, traffic reporters and some websites even announce their locations.

The ticket said the offence was "flashing head beams" in contravention of the HTA, section 169.

Never mind that I have been in the car game for more than 30 years and have never heard the term "head beams."

I checked section 169 and nowhere does it mention radar traps in there.

Sgt. Cam Woolley of the Ontario Provincial Police told me that this law was put in place a few years ago to prevent "civilian" vehicles from impersonating emergency vehicles, notably tow trucks trying to bully their way through traffic to be first on the scene of a wreck.

Nothing at all about radar.

What's more, Diamond's Chevy Tahoe was not producing "alternating"' flashes of light. "Alternating" means one, then the other (just like police cars and other emergency vehicles can do), not both on/both off.

Not only was there no harm, there was no foul.

In our legal system, the legislature passes the laws, the police enforce them. It is not up to the police to make up their own laws – that's what they call a police state.

If the legislature decided in its collective wisdom to make warning of radar speed traps illegal, how hard would it be to pass an unambiguous law to that effect?

I can even help: "It is unlawful to warn other drivers about upcoming radar speed traps; never mind that they don't improve traffic safety."

Okay, the legislature might choose different wording.

The fact is, the legislature has not chosen to pass a law like this, or anything remotely like it.

If Diamond had been standing on the sidewalk holding a neon sign reading, WARNING! RADAR AHEAD!', there would have been nothing the cops could have done.

Needless to say, he decided to fight the ticket.

He contacted the prosecutor, saying the law in question had nothing at all to do with what he allegedly had done, but she said they were going to proceed with the court case.

Okay then, Jan. 10 it would be.

I had a 30-page script ready to go as Diamond's representative. (My dad, who was a lawyer, would have been proud of me. I hope.)

At traffic court, you first present yourself to the prosecutor, who asks how you're going to plead. You'd think anyone who didn't just pay the ticket in the first place and who had shown up at 9 a.m. to fight it would plead not guilty, but some didn't.

You also may have the option of pleading guilty to a lesser charge, which the first case of the morning did.

We were about fourth on the docket.

The prosecutor called Diamond to the bench, asked his name, read the charge, and asked how he pleaded.

"Not guilty, your worship,"' he responded.

Then the prosecutor said, "The police officer has no evidence in this case, your worship."'

"Case dismissed,"' said the justice of the peace.

WHAT? The police officer has "no evidence"? If he had no evidence, why the heck did he lay the charge in the first place?

The fact is, he had no law upon which to base the charge, because Diamond had not done anything illegal.

They assume that you will assume you had in fact done something illegal, fork over your cash, and they smile all the way to the bank.

Now, dad always said that in court, you take a win any way you can. But we were disappointed not to take it to trial so as to set a precedent against this little Buford T. Justice scam by the Toronto Police.

Someone more paranoid than me might suspect they did not want it to go to trial for that very reason, so as not to put their scurrilous behaviour on the trailer for all time.

Now, maybe the "no evidence"' gambit is traffic court shorthand for "the cop didn't show up." But usually with fishing holes, they expect a certain number of people to fight the tickets and schedule the cop for court duty.

I guess we'll never know.

I don't blame the individual cop here, although some of them are clearly overzealous in their pursuit of tickets, quotas, or whatever other pressures they face from their superiors.

But I think it is disgusting that police management sends cops out there to lie in wait to ticket unsuspecting law-abiding citizens when they have to know that what they're ticketing them for is not against the law.

And if they didn't know that before, they sure do now.

Toronto Star

Sunday, October 5, 2008

Blair distancing himself?

Michele Henry Crime Reporter for The Toronto Star

A personality clash between Ontario's two top cops has nothing to do with the Toronto force's decision to pull 28 officers out of a province-wide unit aimed at combating organized crime, officials said yesterday.

Aides for both vehemently deny any head-butting and infighting between Toronto police Chief Bill Blair and OPP Commissioner Julian Fantino led to Blair's recent decision to pull his officers out of certain joint operations.

"I want to put to rest once and for all that there are no personality conflicts," OPP Insp. Dave Ross said. "It has nothing to do with what's transpired."

An internal memo circulated within the Toronto Police Service earlier this week said that starting Dec. 1, officers assigned to five provincial investigative units will report to their superiors in the Toronto force, rather than to the OPP.

The units involve more than dozen police forces across Ontario, include biker and weapons enforcement, illegal gambling, proceeds of crime and auto theft.

This restructuring, the memo says, comes on the heels of OPP proposals to create two joint-force units in Toronto in which local officers would answer to OPP bosses.

A "lack of control," the memo says, over the Toronto force's resources reduces its ability to respond to its own needs.

The memo said both police forces recognize the limitations of the current system, which has often proved ineffective at fighting organized crime.

"How do we get the best results with our resources that are limited?" deputy chief Tony Warr asked yesterday. "We focus them on Toronto priorities. By having our own group, we don't have to do anything that's not Toronto-centric."

That doesn't mean Toronto police are "getting out of the joint forces business," he said. He insisted not much will change beyond whom the officers report to, saying the Toronto force will evaluate when and how to get involved in joint investigations on a case-by-case basis.

Toronto Mayor David Miller praised Blair as an extraordinary chief and said he respects his judgment. Miller waved off any suggestion the move away from joint force operations will diminish the police effort against organized crime.

Since joint operations are provincially funded, Blair's move could prove costly for Toronto police.

Regardless of motive, the restructuring doesn't sit well with Ottawa Police Chief Vernon White, a spokesperson said. "He's pretty disappointed that borders are being created when police organizations should be working together," Const. Alain Boucher said.

"When one (police organization) pulls out, it pulls a string away from us and we have to work differently. When we all work together it becomes a strong unit."

The OPP's Ross said his force remains committed to working with Toronto police to combat organized crime. He said it was premature to speculate how the withdrawal will affect daily operations.

With files from John Spears

A personality clash between Ontario's two top cops has nothing to do with the Toronto force's decision to pull 28 officers out of a province-wide unit aimed at combating organized crime, officials said yesterday.

Aides for both vehemently deny any head-butting and infighting between Toronto police Chief Bill Blair and OPP Commissioner Julian Fantino led to Blair's recent decision to pull his officers out of certain joint operations.

"I want to put to rest once and for all that there are no personality conflicts," OPP Insp. Dave Ross said. "It has nothing to do with what's transpired."

An internal memo circulated within the Toronto Police Service earlier this week said that starting Dec. 1, officers assigned to five provincial investigative units will report to their superiors in the Toronto force, rather than to the OPP.

The units involve more than dozen police forces across Ontario, include biker and weapons enforcement, illegal gambling, proceeds of crime and auto theft.

This restructuring, the memo says, comes on the heels of OPP proposals to create two joint-force units in Toronto in which local officers would answer to OPP bosses.

A "lack of control," the memo says, over the Toronto force's resources reduces its ability to respond to its own needs.

The memo said both police forces recognize the limitations of the current system, which has often proved ineffective at fighting organized crime.

"How do we get the best results with our resources that are limited?" deputy chief Tony Warr asked yesterday. "We focus them on Toronto priorities. By having our own group, we don't have to do anything that's not Toronto-centric."

That doesn't mean Toronto police are "getting out of the joint forces business," he said. He insisted not much will change beyond whom the officers report to, saying the Toronto force will evaluate when and how to get involved in joint investigations on a case-by-case basis.

Toronto Mayor David Miller praised Blair as an extraordinary chief and said he respects his judgment. Miller waved off any suggestion the move away from joint force operations will diminish the police effort against organized crime.

Since joint operations are provincially funded, Blair's move could prove costly for Toronto police.

Regardless of motive, the restructuring doesn't sit well with Ottawa Police Chief Vernon White, a spokesperson said. "He's pretty disappointed that borders are being created when police organizations should be working together," Const. Alain Boucher said.

"When one (police organization) pulls out, it pulls a string away from us and we have to work differently. When we all work together it becomes a strong unit."

The OPP's Ross said his force remains committed to working with Toronto police to combat organized crime. He said it was premature to speculate how the withdrawal will affect daily operations.

With files from John Spears

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

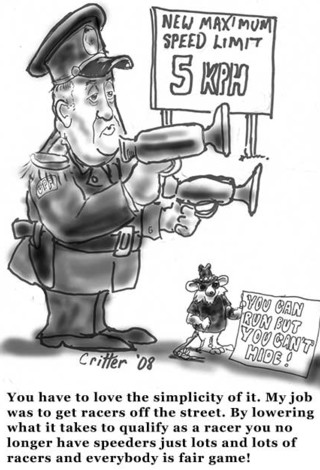

They had No Choice!

They wore these or I took away thier toys for 7 days!

"Damn Street Racer"pays with Brusies